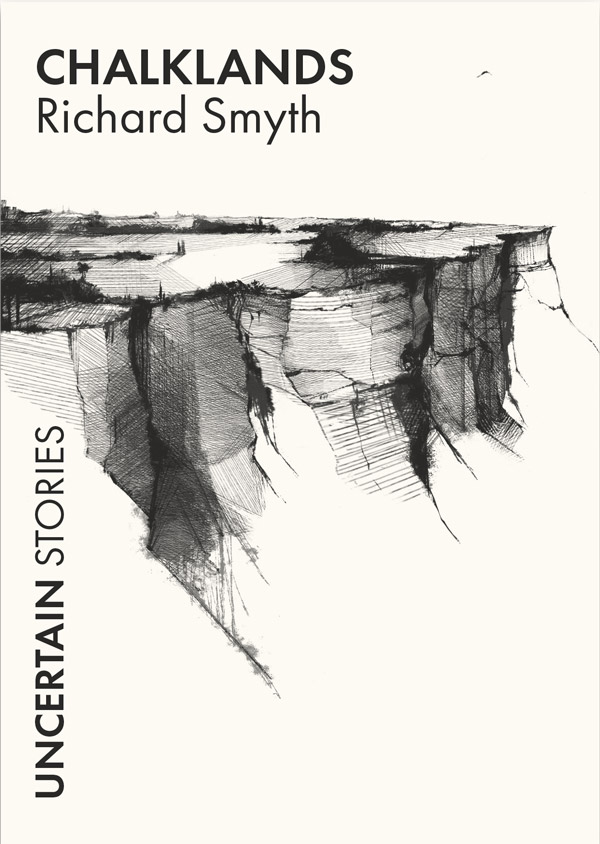

Richard Smyth's short story Chalklands was published in our first set of Little Uncertainties. Here he is to answer some questions for us about reading, writing, and the origins of his story.

Q & A with Richard Smyth

Can you tell us anything about the inspiration behind your story Chalklands?

In a practical sense, I wrote ‘Chalklands’ because a wonderful actress I was working with at the time asked me to write something for her to perform at a Hallowe’en event in the Yorkshire Wolds. So I sat down and started writing and of course wildly overshot the brief and ended up with something that was no use to her at all (but it’s OK, she just wrote something herself, which was much better).

The creative inspiration is, as always, far less easy to pin down. The red kite – the bird that’s the main motif of the story – has interested me for a long time, because they’re rather beautiful, but also rather unsavoury, being indiscriminate scavengers (to be honest, ‘beautiful but unsavoury’ is how I would characterise most of the natural world). The rest of the story just sort of grew from that, in the usual inexplicable ways. Couldn’t tell you quite how I came to start it off with Guy Fawkes’s deep-fried foot.

… to be honest, ‘beautiful but unsavoury’ is how I would characterise most of the natural world …

Alongside your fiction, you’ve also written several non-fiction books and numerous comment pieces and reviews, particularly on subjects connected with the natural world. Our relationship with nature is explored in your fiction too, as it is here in Chalklands. How would you compare the different experiences of writing about these subjects in fiction and non-fiction, and are there perhaps certain themes or ideas that you might prefer to address in one or the other?

Nature is very good for thinking with. It’s wildly, unmanageably complicated, and what it inspires or provokes in us is wildly complicated too – and that’s great for writing, that’s what you need, I think, complication, complexity, richness, abundance (although of course in practical terms the abundance is declining by the day).

What fiction really allows me to do – or rather, what fiction makes easier – is handle ‘nature’, the non-human world, in ways that don’t generate good or right or even complete answers. To me, that’s really what underpins all the themes that I try to deal with in my fiction, the idea that there aren’t answers, there isn’t certainty, in nature, in love, in most aspects of the human experience, nothing is neat, and there are no happy endings (because there are no endings). If there were answers, and if I knew what they were, and if I could type them out in a few dry paragraphs, what would be the point of fiction?

What non-fiction allows me to do, on the other hand, is really get into the finer points of partridge anatomy or suburban ecology or the history of agricultural fascism or whatever it might be, and share them with like-minded weirdos.

But at the bedrock of both things is what I’ve heard called ‘everythingitis’: this itch to just sort of grab hold of everything, all of it, and cram it somehow into books.

What attracts you to writing short stories in general?

They are very easy. People often like to say, oh, short stories are really much harder to write than novels, but I think that’s mostly a thing people say because there’s something rather embarrassing about being caught doing something easy. If it is true then I think they must be doing novels the wrong way. Short stories are easy because they are [checks notes] short, and they don’t really have to go anywhere or do anything, they just have to sort of stand there, being marvellous. Marvellous freaks. So obviously you can explore ideas that are extraordinary and fascinating but wouldn’t sustain a novel, and you can do it in a couple of days. You can take greater risks. You can speak in voices that for one reason or another you couldn’t speak in for 90,000 words. I don’t, for what it’s worth, really favour one form over the other – they’re both just magical things to spend time on. But I know I’ve done things in short stories that novel-writing alone just wouldn’t give me the opportunity to do.

When and where do you most enjoy writing?

I am a very unbohemian writer, in that pretty much every word I write is typed at my desk, on my PC, in a Word document, and nearly everything I write gets written by starting at the start and ending at the end. And because I have a wife who has a proper job and kids who keep school hours I tend to have a pretty unbohemian schedule, too. Sorry! But of course, a good three-quarters of the work is back-office processes – whatever’s going on inside, while I’m doing other things.

Moving on to your own reading, what’s your ideal time and place to read?

In my younger days I would have said anywhere, any time, but nowadays I have a definitive answer: in the afternoon, in the pub. If I sit down in a quiet room at home I will – whatever my intentions – almost immediately fall asleep. So the afternoon pub provides a quiet, comfortable alternative. Also they have crisps. And there is, what’s more, a very special, faintly euphoric moment of heightened insight that comes roughly between the first and second pints.

Chalklands is part of our Little Uncertainties project here at Uncertain Stories, through which we’re distributing free short story booklets to readers (and potential readers!) across the country through cafes and bookshops. If you could give copies of one short story – classic or modern – to everybody in your own home town, which story would you choose, and why?

I think there are very delicate, carefully structured, emotionally restrained, beautifully balanced Fabergé egg-type stories, and there are demented, incontinent, what-the-hell-are-you-doing short stories, and if I have to choose I’m going with the latter, because everyone in every town needs more of that sort of thing. I can’t settle on one though. Either Gogol’s The Nose or Peter Carey’s Life and Death in the South Side Pavilion or Frankenstein's Monster is Drunk, and the Sheep Have All Jumped the Fences by Owen Booth.

Do you have a favourite memory of reading a book or story? Maybe a moment that really left an impression on you?

This is a really interesting question, because I’m intrigued by the ways in which the physical act of reading interacts or connects with or counteracts the emotional and intellectual process of reading. I’m sure I have terribly skewed views on a lot of books because of the context in which I read them. I have very rich and pleasant memories of, say, reading Germinal on a ferry to France or pulling an all-nighter to finish Midnight’s Children when I was 19 – but that’s a bit precious, isn’t it? The one book more than any other than I remember finishing and feeling like, whump, the book had sort of landed on me from a great height, was Pale Fire.

I’m sure I have terribly skewed views on a lot of books because of the context in which I read them.

Finally, do you have a favourite independent bookshop you think people should visit?

Ah well they’re all terrific, aren’t they? The Bookshop On The Square in Otley, The Grove in Ilkley, The Bound in Whitley Bay, Darling Books in Horbury, Cogito in Hexham, Colours May Vary in Leeds. People should go to all of those (and ask them for my books).

£

£